- Home

- Meredith May

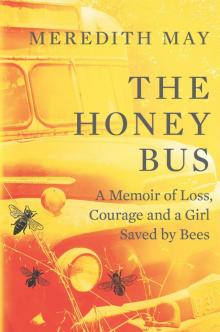

The Honey Bus

The Honey Bus Read online

An extraordinary story of a girl, her grandfather and one of nature’s most mysterious and beguiling creatures: the honeybee.

Meredith May recalls the first time a honeybee crawled on her arm. She was five years old, her parents had recently split and suddenly she found herself in the care of her grandfather, an eccentric beekeeper who made honey in a rusty old military bus in the yard. That first close encounter was at once terrifying and exhilarating for May, and in that moment she discovered that everything she needed to know about life and family was right before her eyes, in the secret world of bees.

May turned to her grandfather and the art of beekeeping as an escape from her troubled reality. Her mother had receded into a volatile cycle of neurosis and despair and spent most days locked away in the bedroom. It was during this pivotal time in May’s childhood that she learned to take care of herself, forged an unbreakable bond with her grandfather and opened her eyes to the magic and wisdom of nature.

The bees became a guiding force in May’s life, teaching her about family and community, loyalty and survival and the unequivocal relationship between a mother and her child. Part memoir, part beekeeping odyssey, The Honey Bus is an unforgettable story about finding home in the most unusual of places, and how a tiny, little-understood insect could save a life.

Meredith May

The Honey Bus

A Memoir of Loss, Courage and a Girl Saved by Bees

For Grandpa

E. Franklin Peace

1926–2015

Contents

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

Further Reading

Photos

“So work the honeybees, creatures that by a rule in nature teach the art of order to a peopled kingdom.”

—William Shakespeare, Henry V

PROLOGUE

Swarm

1980

Swarm season always arrived by telephone. The red rotary phone jangled to life every spring with frantic callers reporting honeybees in their walls, or in their chimneys, or in their trees.

I was pouring Grandpa’s honey over my corn bread when he came out of the kitchen with that sly smile that said we’d have to let our breakfast go cold again. I was ten, and had been catching swarms with him for almost half my life, so I knew what was coming next. He slugged back his coffee in one gulp and wiped his mustache with the back of his arm.

“Got us another one,” he said.

This time the call came from the private tennis ranch about a mile away on Carmel Valley Road. As I climbed into the passenger seat of his rickety pickup, he tapped the gas pedal to coax it to life. The engine finally caught and we screeched out of the driveway, kicking up a spray of gravel behind us. He whizzed past the speed limit signs, which I knew from riding with Granny said to go twenty-five. We had to hurry to catch the swarm because the bees might get an idea to fly off somewhere else.

Grandpa careened into the tennis club and squealed to a stop near a cattle fence. He leaned his shoulder into his jammed door and creaked it open with a grunt. We stepped into a mini-cyclone of bees, a roaring inkblot in the sky, banking left and right like a flock of birds. My heart raced with them, frightened and awestruck at the same time. It seemed like the air was throbbing.

“Why are they doing that?” I shouted over the din.

Grandpa bent down on one knee and leaned toward my ear.

“The queen left the hive because it got too crowded inside,” he explained. “The bees followed her because they can’t live without her. She’s the only bee in the colony that lays eggs.”

I nodded to show Grandpa that I understood.

The swarm was now hovering near a buckeye tree. Every few seconds, a handful of bees darted out of the pack and disappeared into the leaves. I walked closer, and looked up to see that the bees were gathering on a branch into a ball about the size of an orange. More bees joined the cluster until it swelled to the size of a basketball, pulsating like a heart.

“The queen landed there,” Grandpa said. “The bees are protecting her.”

When the last few bees found their way to the group, the air became still again.

“Go wait for me back by the truck,” Grandpa whispered.

I leaned against the front bumper, and watched as he climbed a stepladder until he was nose-to-nose with the bees. Dozens of them crawled up his bare arms as he sawed the branch with a hacksaw. Just then a groundskeeper started up a lawn mower, startling the bees and sending them back into the air in a panic. Their buzz rose to a piercing whine, and the bees gathered into a tighter, faster circle.

“Dammit all to hell!” I heard Grandpa cuss.

He called out to the groundskeeper, and the mower sputtered off. While Grandpa waited for the swarm to settle back down into the tree, I felt something crawling on my scalp. I reached up and touched fuzz, and then felt wings and tiny legs thrashing in my hair. I tossed my head to dislodge the bee, but it only became more tangled and distressed, its buzz rising to the high pitch of a dentist’s drill. I took deep breaths to brace for what I knew was coming.

When the bee buried its stinger in my skin, the burn raced in a line from my scalp to my molars, making me clench my jaw. I frantically searched my hair again, and stifled a scream as I discovered another bee swimming in my hair, then another, my alarm radiating out wider and wider from behind my rib cage as I felt more fuzzy lumps than I could count, a small squadron of honeybees struggling with a terror equal to my own.

Then I smelled bananas—the scent bees emit to call for backup—and I knew that I was under attack. I felt another searing prick at my hairline followed by a sharp pierce behind my ear, and collapsed to my knees. I was fainting, or maybe I was praying. I thought that I might be dying. Within seconds, Grandpa had my head in his hands.

“Now try not to move,” he said. “You’ve got about five more in here. I’ll get them all out, but you might get stung again.”

Another bee stabbed me. Each sting magnified the pain until it felt like my scalp was on fire, but I grabbed the truck tire and hung on.

“How many more?” I whispered.

“Just one,” he said.

When it was all over, Grandpa took me into his arms. I rested my pounding head on his chest, which was muscled from a lifetime of lifting fifty-pound hive boxes full of honey. He gently placed his calloused hand on my neck.

“Your throat closing up?”

I showed him my biggest inhale and exhale. My lips felt oddly tingly.

“Why didn’t you call out to me?” he asked.

I didn’t have an answer. I didn’t know.

My legs were shaky, and I let Grandpa carry me to the truck and place me on the bench seat. I’d been stung before, but never by this many bees at once, and Grandpa was worried that my body might go into shock. If my face swelled up, he said, I might have to go to the emergency room. I waited with instructions to honk the horn if I couldn’t breathe as he finished sawing the branch. He shook the bees into a white wooden box and carried it to the truck bed while I reached up and checked the hot lumps on my scalp. They were tight and hard, and it se

emed like they were getting bigger. I worried that pretty soon my whole head would be puffed out like a pumpkin.

Grandpa hustled back into the truck and started the engine.

“Just a minute,” he said, taking my head in his hands and exploring my scalp with his fingers. I winced, certain he was pressing marbles into my head.

“Missed one,” he said, drawing a dirty fingernail sideways across my scalp to remove the stinger. Grandpa always said that squeezing the stinger between your thumb and finger is the worst way to pull it out, because it pushes all the venom into you. He held out his palm to show me the stinger with the pinhead-sized venom sac still attached.

“It’s still going,” he said, pointing to the white organ flexing and pumping venom, oblivious that its services were no longer needed. It was gross, and made me think of a chicken running with its head cut off, and I wrinkled my nose at it. He flicked it out the window and then turned to me with a pleased look, like I had just shown him my report card with all A’s.

“You were very brave. You didn’t panic or nothin’.”

My heart cartwheeled in my chest, proud of myself for letting the bees sting me without screaming like a girl.

Back home, Grandpa added the box of bees to his collection of a half dozen hives along the back fence. The swarm was ours now, and would settle into its new home soon. Already the bees were darting out of the entrance and flying in little circles to explore their surroundings, memorizing new landmarks. In a few days’ time, they would be making honey.

As I watched Grandpa pour sugar water into a mason jar for them, I thought about what he had said about the bees following the queen because they can’t live without her. Even bees needed their mother.

The bees at the tennis ranch attacked me because their queen had fled the hive. She was vulnerable, and they were trying to protect her. Crazy with worry, they’d lashed out at the nearest thing they could find—me.

Maybe that’s why I hadn’t screamed. Because I understood. Bees act like people sometimes—they have feelings and get scared about things. You can see this is true if you hold very still and watch the way they move, notice if they flow together softly like water, or if they run over the honeycomb, shaking like they are itchy all over. Bees need the warmth of family; alone, a single bee isn’t likely to make it through the night. If their queen dies, worker bees will run frantically throughout the hive, searching for her. The colony dwindles, and the bees become dispirited and depressed, sluggishly wandering the hive instead of collecting nectar, killing time before it kills them.

I knew that gnawing need for a family. One day I had one; then it was gone overnight.

Not long before my fifth birthday, my parents divorced and I suddenly found myself on the opposite coast in California, squeezed into a bedroom with my mom and younger brother in my grandparents’ tiny house. My mother slipped under the bedcovers and into a marathon melancholy, while my father was never mentioned again. In the empty hush that followed, I struggled to make sense of what had happened. As my list of life questions grew, I worried about who was going to explain things to me.

I began following Grandpa everywhere, climbing into his pickup in the mornings and going to work with him. Thus began my education in the bee yards of Big Sur, where I learned that a beehive revolved around one principle—the family. Grandpa taught me the hidden language of bees, how to interpret their movements and sounds, and to recognize the different scents they release to communicate with hive mates. His stories about the colony’s Shakespearean plots to overthrow the queen and its hierarchy of job positions swept me away to a secret realm when my own became too difficult.

Over time, the more I discovered about the inner world of honeybees, the more sense I was able to make of the outer world of people. As my mother sank further into despair, my relationship with nature deepened. I learned how bees care for one another and work hard, how they make democratic decisions about where to forage and when to swarm, and how they plan for the future. Even their stings taught me how to be brave.

I gravitated toward bees because I sensed that the hive held ancient wisdom to teach me the things that my parents could not. It is from the honeybee, a species that has been surviving for the last 100 million years, that I learned how to persevere.

1

Flight Path

February 1975

I didn’t see who threw it.

The pepper grinder flew end over end across the dinner table in a dreadful arc, landing on the kitchen floor in an explosion of skittering black BBs. Either my mother was trying to kill my father, or it was the other way around. With better aim it could have been possible, because it was one of those heavy mills made of dark wood, longer than my forearm.

If I had to guess, it was Mom. She couldn’t stand the silence in her marriage anymore, so she got Dad’s attention by hurling whatever was within reach. She ripped curtains from rods, chucked Matthew’s baby blocks into walls and smashed dishes on the floor to make sure we knew she meant business. It was her way of refusing to become invisible. It worked. I learned to keep my back to the wall and my eyes on her at all times.

Tonight, her pent-up fury radiated off her body in waves, turning her alabaster skin a bright pink. A familiar dread pooled in my belly as I held my breath and studied the wallpaper pattern of ivy leaves winding around copper pots and rolling pins, terrified that the slightest sound from me would redirect the invisible white-hot beam between my parents and leave a puff of smoke where once a five-year-old girl used to be. I recognized this stillness before the storm, the momentary pause of utensils held aloft before the verbal car crash to come. Nobody moved, not even my two-year-old brother, frozen mid-Cheerio in his high chair. Dad calmly set down his fork and asked Mom if she planned to pick that mess up.

Mom dropped her paper napkin on top of her untouched dinner; we were eating American chop suey again—an economical mishmash of elbow macaroni, ground beef and whatever canned vegetables we had, mixed with tomato sauce. She lit a cigarette, long and slow, and then blew smoke in Dad’s direction. I expected him to take his normal course of action, to unfold his long body from the chair, disappear into the living room and crank the Beatles so loud that he couldn’t hear her. But tonight he just stayed seated, arms crossed, his coal-colored eyes boring at Mom through the smoke. She flicked her ash into her plate without breaking his stare. He watched her, disgust etched into his face.

“You promised to quit.”

“Changed my mind,” she said, inhaling so deeply I could hear the tobacco crackle.

Dad slapped the table and the silverware clattered. My brother startled, then his lower lip curled down and his breath hitched as he wound up for a full-body cry. Mom exhaled in Dad’s direction again and narrowed her eyes. My nerves hopped like a bead of water in a frying pan as I nervously tapped my fingers on my thigh under the table, counting the seconds as I waited for one of them to pounce. When I counted to seven, I noticed the beginnings of a sardonic smile at the corners of Mom’s mouth. She stubbed her cigarette out on her plate, rose and sidestepped the peppercorns, then stomped into the kitchen. I heard her banging pots, and then a lid clattered to the ground, ringing a few times before it settled on the floor. She was up to something, and that was never good.

Mom returned to the table with a steaming pot, still warm from the stove. She lifted it over her head and I screamed, worried she would burn Dad dead. He screeched his chair back, stood up and dared her to throw it. My stomach lurched, as if the table and chairs had suddenly lifted off the floor and spun me too fast like one of those carnival teacup rides.

I closed my eyes and wished for a time machine so I could go back to just last year, when my parents still talked to each other. If I could just pinpoint that moment right before everything went wrong, I could fix it somehow and prevent this day from ever happening. Maybe I’d show them the forgotten box of Kodachrome slides in the baseme

nt, the evidence that they loved each other once. When I first held the paper squares to the sunlight, I’d discovered that Mom’s face was once full of laughter, and she used to wear short dresses and shiny white boots and smoke her cigarettes through a long stick like a movie star. She still had the same short boy haircut, but it was a brighter shade of red then, and her eyes seemed more emerald. In every slide Mom was smiling or winking over her shoulder at Dad. He took the photos not long after he’d spotted her registering for classes at Monterey Peninsula College, and invited her for a drive down the coast to Big Sur.

He’d recognized her from a few summer parties. She had been the one with the loud laugh, the funny one with a natural audience always in tow. He noticed how easily she flowed in a crowd of strangers, which drew my quiet father out of the corners. He was raised never to speak unless spoken to, and liked to study people before deciding to talk to them. This made him slightly mysterious to my mother, who was drawn by the challenge of getting the tall stranger with the dramatic widow’s peak and smoky eyes to open up. When he told her his plan to join the navy and travel abroad after college, Mom, who had never been outside California, was sold.

They married in 1966, and within four years the navy relocated them to Newport, Rhode Island, where Matthew and I were born. After his service, Dad worked as an electrical engineer, making machines that calibrated other machines. Mom took us on strolls to the butcher and the grocery store, and made sure dinner was on the table at five. On the outside, our lives seemed neat, organized, on track. We lived in a wood-shingled row apartment, and my brother and I had our own rooms on the second floor, connected by a trail of Lincoln Logs and Lite-Brite pins and gobs of Play-Doh dropped where we’d last used them. Dad installed a swing on the front porch, and we played with the neighbor kids who lived in the three identical homes attached to ours. On weekend mornings, Dad came into my room and we identified clouds as they passed my bedroom window, pointing out the dinosaurs and mushrooms and flying saucers. Before going to sleep, he read to me from Grimm’s Fairy Tales, and even though every story ended in a violent death of some kind, he never said I was too little to hear such things.

The Honey Bus

The Honey Bus